|

From Charles Dickens to Philip Pullman, the rugged beauty of East Anglia has inspired some of our best-known authors. Victoria Manthorpe follows in the footsteps of these literary greats.

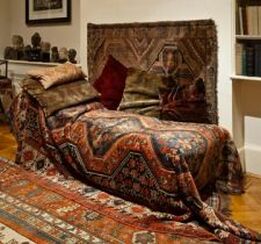

Pablo Picasso was born on October 25th 1881 at house No 15 in Plaza de la Merced, Malaga. The family lived in a third floor apartment with a grandmother and maternal aunts; with two sisters and a brother to come, there can have been little room to spare. The building is still there but nothing remains of the original interior; instead, the curators offer displays of artefacts and some furnishings that suggest or are similar to what is known of his home. Why visit a birthplace? What can it tell us that isn’t available in a biography? The most obvious answer is the physical and visual impact of the building and the surrounding area. Plaza de la Merced is in a central area of Malaga. The houses are tall, generously proportioned and well mannered with shutters and balconies. This would have been a pleasant environment with a sense of status but also with close neighbours and a community. And what could be more nurturing and secure than the sunny climate …that brightness of the blue sky and the reliable heat. There is no dourness here.  Picasso’s father, Don Jose Ruiz, was a technically competent but uninspired painter of still lifes who taught at the School of Fine Arts and was a curator of the municipal collection. I cannot remember ever having seen an example of his work before. But here in the house many of his canvasses have been gathered together with some of Picasso’s earliest works. They bring home the fact that Picasso was born into a world saturated with art and painting. And some of his subjects – doves in particular – are there in his childhood. Of the various artefacts – the christening gown, the documentation, photographs – little comes to life. Young Pablo lived here for only his first 10 years before the family moved to La Corunna and then to Barcelona. Still those first ten years are very important. Picasso’s first school was just round the corner and close to his father’s place of work. He did not like school and often played truant. He was both too clever and already too interested in art. But that close proximity and the maze of narrow streets that make up the old centre of Malaga, and the ships and coast near by – all help to give one a feeling of Picasso’s beginnings – what he saw at an early age – and what contributed to his felt experience. Birthplaces are one thing and endings are another. There may be a trajectory but we do not have to be defined by our beginnings and Picasso certainly was not. However modest our talents by comparison, still, like him we can choose to be defined by our potential. To the Freud Museum – 20 Maresfield Gardens – my first visit. I was surprised to find it was just a few houses away from where I once went to school. Freud died in 1939, a decade before I was born, but his daughter Anna would still have been living and analysing there when I was skipping down the road. Sigmund’s study is on the ground floor. This is the big attraction – to see where the great man worked – the desk, the couch and the antiquities. The desk has a special chair designed by the architect Felix Angenfield to help Sigmund maintain his habitual posture for reading. Because of its shape with a high protruding back to support the Freudian head, it looks rather like a person in its own right: an abstracted mannequin to represent the doctor at work. When he looked up from his reading or writing he would have seen on the opposite wall a lithograph of Andre Brouillet’s painting of Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot presenting an hysterical female patient to his class of students. The patient is arching back in a posture that was apparently common to her condition. Her position as the only woman in the room and the disarray of her bodice attests to the woman hysteric’s situation in 19th century society – defined by male doctors and subjected, at least in this representation, to the male gaze. The painter has left open the degree of prurience with which she is viewed to individual experience. This is a very active museum and on the day I was there a member of the staff was giving very a scholarly commentary on the history of hysteria.  From the Freud Museum website From the Freud Museum website The word ‘iconic’ is flung around rather freely these days. But the couch covered with its richly red oriental carpet cover is definitely iconic – no mistake. On this couch, exactly here on this piece of furniture, was where the great new exploration of the unconscious through the ‘talking cure’ began. As has been noted before, this was a magic carpet into an internal world. The many hundreds of mostly small antiquities, of which Freud was a fervent collector, are distributed around the room on shelves, tables and within vitrines. Their origins are Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Far Eastern – some copies some originals, some bought, some given, some found – all of interest to the archaeological preoccupations of Dr Freud. So this is a museum twice over. But this is not the room that all these artefacts originally occupied. They were all delivered out of Vienna in 1938 from Bergasse 19, the apartment where the family lived and Freud worked. This room in Maresfield Gardens is a recreation, a staging, of an important moment in European cultural history. There are a number of writer’s studies that have been preserved after their death (Thomas Hardy, for example) but here Freud not only had the intention of preserving it just so, but also transported it across Europe, his personal stage set. Freud and his family have curated his history. But as the Guide Book says: ‘Freud cannot be reduced to a private individual’ and then adds a quote from W.H. Auden: ‘he has become a climate of opinion.’ Earlier in the day I had visited Lord Leighton’s house in Kensington. He had no immediate family, and after his death all his possessions were sold. So much of what there is on view has had to be recreated including parts of the famous Arabian décor. Many of the rooms are used for an exhibition of paintings by Lawrence Alma Tadema, and including some by his wife Laura. The Alma Tademas are far more present than Frederic Leighton. Alma Tadema’s huge extravagant canvases of classical scenes have been a tremendous source of dramatic reference for filmmakers and, so, are once more in vogue. Who would have thought, fifty or sixty years ago, that Alma Tadema, a once distained Victorian painter, would create such interest? Public taste is an odd thing. June 2017 - EDP Norfolk '50 Years on From the Summer of Love' The Hippie Counter Culture in East Anglia I really enjoyed researching this article and meeting up with people who were young and hip in Norwich in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

More on the Haunted Hotel project coming up soon. Filming goes ahead on the little ghost story ' Room 27b' early in July. Meanwhile, I'm preparing a paper for the SISJAC Conference on The Western Merchants in East Asia in the nineteenth century to be held at the Sainsbury Institute, Norwich on June 22-23. I'm really looking forward to meeting historians who specialise in this area. The Bloomsbury Group of modernist artists and writers has long attracted the highest literary and critical attention. But Bloomsbury has also become a literary industry fed by a seemingly endless stream biographies, memoirs, recreations, discourses, semi-fiction, and television and film dramas. And there seems to be no end to the descendants and friends of the members of the group who are ready to join the production line. But here is an alternative for you: the Meynells, their family and circle - The Bayswater Group! At the heart of the group are the writers Alice Meynell née Thompson (1847-1922) and her publisher husband Wilfrid Meynell. Alice’s sister Elizabeth (Mimi) Butler (1846-1933) was a leading battle painter of the mid Victorian period. Alice and Mimi were daughters of the concert pianist Christiana Weller and Thomas Thompson, a gentleman of the West Indies. They were raised in the wild landscape and barely accessible villages of the Ligurian littoral and ‘finished’ in the artistic salons of Kensington. Thompson’s fortune came from sugar and slavery and he himself was illegitimately descended from a Creole woman. This was quite a different colonialism from the Jackson’s (Virginia’s mother) and Strachey’s India. Both Alice and Mimi adored the landscape and culture of their Mediterranean upbringing and both converted to Catholicism. Not for them a ‘room of one’s own’. Both shared their space with large, loving families. Alice’s poetry and essays made her internationally famous and she toured and lectured extensively. She also raised eight children. Alice and Wilfrid’s home at 47 Palace Court W2 became a nexus for the London literati a generation before Bloomsbury but overlapping with it. The Meynell’s rescued the destitute poet Francis Thompson and supported the novelist George Meredith. Alice was a political radical and supporter of the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Is it possible that Catholicism, with its acknowledgment of the spiritual feminine in the person of the Virgin Mary, contributed more possibility of cultural development for a woman than Protestantism or atheism? Now here’s the challenge to Bloomsbury. In the midst of a patriarchal culture, inspired by and in dialogue with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Alice found a purely female literary voice. The critic Tala Schaffer suggests that Virginia Woolf deliberately suppressed Meynell’s influence on her – instead promoting herself as the founder of the female literary tradition. Schaffer accuses Woolf of subverting and appropriating the past in an act of ‘modernist self-fashioning’[1]. Having been extraordinarily famous for her battle paintings (The Roll Call, Scotland Forever, The Remnants of an Army), Mimi gave up her public work when she married the maverick army officer William Butler although sketchbooks from later years survive.. Two of Alice and Wilfrid’s children, Francis (1891-1975) and Viola (1885-1956), carried on the literary work. Francis worked as a poet and printer, Viola as a novelist and poet. It was Viola who gave refuge to and helped DH Lawrence in his early difficult times. Alice Meynell, like Virginia Woolf, suffered from depression. [1] Writing a Public Self: Alice Meynell’s ‘Unstable Equilibrium’ in Women’s Experience of Modernity. Ann Ardis and Leslie Lewis (eds) (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. 2003) pp18, 2. Quoted by Ann Ardis in Modernism and Cultural Conflict 125.

|

Victoria Manthorpeauthor and feature writer Blog

Your email will only ever be used to send you new posts and you can unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please check Victoria's privacy statement.

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|