|

Thank you to biographer Evelyn Toynton[i] for responding to the previous blog about people associated with the rectory at Booton in Norfolk. Apparently, Jean Rhys stayed there for about six months during WWII, having been taken in by the kindly Reverend Willard Feast. According to Rhys’s biographer, Carole Angier, (Jean Rhys: Life and Work 1985) Rhys often made life hell for the Reverend and his family, even, on one occasion verbally attacking his 13-year-old daughter so that the poor girl was reduced to tears. The source of this story was a family friend of the Feasts, one Eric Griffiths. If anyone knows more about this or other tales of Booton do, please, email me. This month I’ve been re-reading The Art of Literary Biography (1995) edited by John Batchelor. Two topics struck me particularly: Ann Thwaite’s chapter ‘Starting Again’ raised the problem of choosing a subject for a biography and Catherine Peters argued for the importance of ‘Secondary Lives’ as the context of biographical study. Thwaite discusses the various reasons for an author’s choice of subject, including both conscious and unconscious attraction but concludes, with Hilary Spurling, that it is more often an arranged marriage than an affair of the heart. Colleagues, tutors, and publishers are often the prompt for a subject. The results are certainly not necessarily the worse for that. But as Ann points out if you are going to spend years of your mental life immersed in a person’s life and work you need to choose carefully. Traditionally the subjects are people of singular achievement or prestige: the high-profile, individual. But latterly there are many examples of what Catherine Peters calls ‘Secondary Lives’. Examples are Claire Tomalin’s The Invisible Woman (1995) about Dickens’ mistress, Nelly Ternan, or Jo Manton’s Claire Claremont and the Shelleys (1992), and Thwaite’s The Poet’s Wife (1996) about Emily Tennyson. We are more and more inclined to see these people as far from ‘secondary’ and Peters certainly supports the trend believing that these other characters in the drama of a celebrity life can shift our perceptions both of the individual and of the times. The satellites are not always women spinning around the planet of a man. Virginia Woolf broke new ground here as in so many things with her comic Flush: A Biography (1933) about Elizabeth Browning’s dog. More recently Michael O ‘Hagan produced the highly entertaining The Life and Opinions of Maf the Dog (2010) – the views of Marilyn Monroe’s pet. But I am more concerned with the family or group dynamic from which a biographical subject emerges. Tim Parks in his The Novel: A Survival Skill (2015) has drawn on systemic psychology – the study of family value structures – to analyse the fiction of Joyce, Lawrence, Hardy and Dickens. He proposes that their novels contain the biographies of their family patterns. He based his theory largely on Valeria Ugazio’s Semantic Polarities and Psychopathologies in the Family (2013). Ugazio cites four dominant semantics active in family life which lead to four pathologies: the semantics of power lead to anorexia and bulimia, the semantics of good and evil lead to obsessive compulsive disorders, the semantics of freedom lead to phobic disorders and the semantics of belonging lead to depression. It’s an excellent book – as is Tim Park’s - and I wonder about the possibility of using systemic psychology to study family biography. Why are there often two or even three promising individuals in a family – the Durrells – Laurence and Gerald, the Flemings - Ian and Peter, the Spencers - Stanley and Gilbert - but one who pulls ahead to the finish line? And what of the families whose talents span the generations – the du Mauriers, the Freuds, the Thackerays - who wins, who loses in the emotional stakes of family life. Why are there tragic failures side-by-side with ‘successes – Branwell Bronte and his sisters, Edith Cavell’s brother Leonard crushed by the ethos that made her? The question of why none of Charles Dickens’ children stood a chance of finding their own success is examined in Tim Parks’ book. For me the compelling question is to what extent people make themselves and to what extent they are made by a group or a family dynamic. [i] Evelyn Toynton is the biographer of Jackson Pollock (2012) and lives in Norfolk.

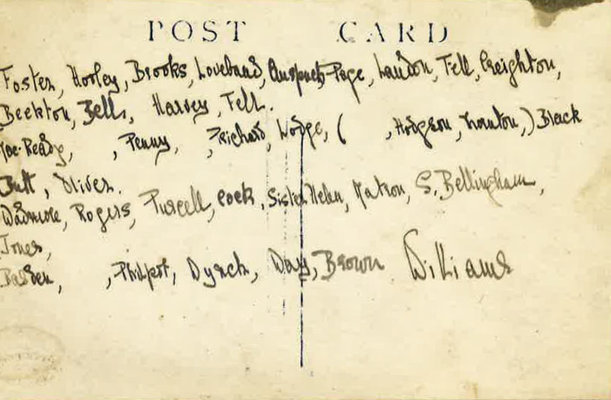

Richard Holme has sent me these pictures of Exmouth VAD nurses and the interior of the hospital. The key at the back shows Doris 'Page' on the top row – so it is before her death. I haven’t yet been able to identify Lilias Haggard but there are several unnamed nurses so she may be there.

May 8 2016 ___________________________ Recently I made a visit with a friend to Booton church near Reepham. This is part of an on-going traipse, wander, drift around Norfolk churches which, on account of the numbers of destinations, has, happily, no apparent end. We usually manage three churches in one trip – it being useful to compare the styles and provision in adjacent villages. But sometimes we just do one before retreating for a pub lunch. Booton was reconstructed in the late 19th century by the Rev Whitwell Elwin (1816-1900) whose family were long-time lords of the manor in the area. Elwin was a singular character and the exuberant dreadfulness of his design for the church together with the reminder that he was friendly with the Lytton family nudged me to investigate him a little further. In particular, the guide book mentions that one of the stained glass windows of angels includes the faces of what he called his ‘blessed girls’. It didn’t take long to order up Emily Lytton’s A Blessed Girl (London: 1953). When I read it many years ago I didn’t know anything about Booton or Elwin so this reading was fresh – and much more intriguing. The book is Emily’s own creation from a large collection of letters written between her and ‘his Rev’ as she called him. The correspondence begins when she was thirteen and continues through her courtship and marriage, to Edwin Lutyens until Elwin’s death in 1900. The book comes with an introduction from her daughter Mary Lutyens – herself a well-known memoirist and writer. From papers in the Norfolk Record Office I discovered an obituary, notes by Noel Spencer and Kate Weaver and a 1971 booklet by the Rev. Feast from which I discovered that Elwin had several children of his own of whom one son died of pleurisy in 1874 and the following year a daughter died of anaemia. Two other sons are noted – one became a vicar at Worthing, the other a missionary father in India. Elwin was reputedly short of stature but strong willed and fond of animals. The rectory which he built close to the church included spacious reception rooms for entertaining his illustrious friends but the rest of the house was never finished – unpainted walls, no curtains, little furniture but multitudes of books. In his younger days he had been a Whiggish editor of a High Tory journal, and was a friend of Trollope, Forster and Thackeray. Having been advised against seeking preferment in the church (because it led to an uncomfortable life) the ebullient Elwin was effectively beached in Booton - rather too large a figure for the small Norfolk world. The County came to hear his sermons, which he delivered with his eyes closed, but the poor of the village were steadfastly unimpressed. There was little or no music at his services and communion comprised wine from a bottle, opened there and then with a corkscrew, and a loaf of bread. It was through his literary connections that he had met Edward Bulwer Lytton, the novelist, and his son Lord Robert Lytton a poet and diplomat who was Emily’s father. Elwin was a great conversationalist with a store of anecdotes and references at his fingertips and the Lyttons took to him. He became the confidant of the whole family – both of Emily’s parents, separately, and her older sister Betty had confessional correspondence with him and relied on his advice. Two things strike me. One is the acceptance by everyone in Emily’s family that this friendship with a man 58 years her senior was suitable. It is clear that Elwin acted as a counsellor and moral advisor to Emily in her developing years, yet today we might also look for sublimated motives. Emotionally Emily relied on his letters to help her through the traumas of growing-up in a troubled household (her mother was widowed young and her income uncertain). Elwin must have spent a considerable amount of time on his letter writing and there is some indication that it irritated his wife. Two, there is open discussion in these letters of Emily’s passion in her late teens and early twenties for Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his attempts to seduce her. Blunt was a poet, an Arabist, and father of Emily’s best friend Judith. Emily was his social equal – not the governess or maid servant whom we have come to regard as the usual victims of predatory Victorian males. Emily had to conceal this passion from her mother and in the end it was Judith who confronted her own father about his low intentions – an extraordinary scene to imagine and not part of the usual vocabulary we have for the Victorian ‘miss’. The letters reveal Emily responding whole-heartedly and frankly to the one-to-one intimate attention of ‘the Rev’. She didn’t, sadly, find a similar relationship with her husband – the much admired Edwardian architect. But she did find another passion later in life for Theosophy and Krishnamurti which took her back to the India of her childhood when her father had been Viceroy of India. And Elwin – how much was he living vicariously in his long and ardent correspondences? Certainly the tone is always moral and Christian but also very fond. Emily called his endearments ‘sugar’. She visited him often at Booton where as a country parson his life was constricted by parish matters.. Through Emily’s life amongst the aristocracy, visiting the great houses of Knowsley and Hatfield, he was able to savour a wider world that kept him in contact with the important people of his day. One cannot help reflecting on the cumulative and intense power of letter writing to develop the affections, as well as to cultivate moral habits. It would be interesting to find out the identity of Elwin’s other ‘blessed girls’ - one was Emily’s sister Betty, another may have been Miss EA Holley of Green Lane House, Reepham. The next step would be to match them up with the angelic faces in Booton’s stained glass windows. It has been suggested that A.E. Booker RA was the designer. Comments and further information welcomed. ©Victoria Manthorpe April 14 2016 ---End--- |

Victoria Manthorpeauthor and feature writer Blog

Your email will only ever be used to send you new posts and you can unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please check Victoria's privacy statement.

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|