|

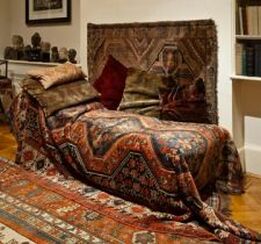

To the Freud Museum – 20 Maresfield Gardens – my first visit. I was surprised to find it was just a few houses away from where I once went to school. Freud died in 1939, a decade before I was born, but his daughter Anna would still have been living and analysing there when I was skipping down the road. Sigmund’s study is on the ground floor. This is the big attraction – to see where the great man worked – the desk, the couch and the antiquities. The desk has a special chair designed by the architect Felix Angenfield to help Sigmund maintain his habitual posture for reading. Because of its shape with a high protruding back to support the Freudian head, it looks rather like a person in its own right: an abstracted mannequin to represent the doctor at work. When he looked up from his reading or writing he would have seen on the opposite wall a lithograph of Andre Brouillet’s painting of Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot presenting an hysterical female patient to his class of students. The patient is arching back in a posture that was apparently common to her condition. Her position as the only woman in the room and the disarray of her bodice attests to the woman hysteric’s situation in 19th century society – defined by male doctors and subjected, at least in this representation, to the male gaze. The painter has left open the degree of prurience with which she is viewed to individual experience. This is a very active museum and on the day I was there a member of the staff was giving very a scholarly commentary on the history of hysteria.  From the Freud Museum website From the Freud Museum website The word ‘iconic’ is flung around rather freely these days. But the couch covered with its richly red oriental carpet cover is definitely iconic – no mistake. On this couch, exactly here on this piece of furniture, was where the great new exploration of the unconscious through the ‘talking cure’ began. As has been noted before, this was a magic carpet into an internal world. The many hundreds of mostly small antiquities, of which Freud was a fervent collector, are distributed around the room on shelves, tables and within vitrines. Their origins are Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Far Eastern – some copies some originals, some bought, some given, some found – all of interest to the archaeological preoccupations of Dr Freud. So this is a museum twice over. But this is not the room that all these artefacts originally occupied. They were all delivered out of Vienna in 1938 from Bergasse 19, the apartment where the family lived and Freud worked. This room in Maresfield Gardens is a recreation, a staging, of an important moment in European cultural history. There are a number of writer’s studies that have been preserved after their death (Thomas Hardy, for example) but here Freud not only had the intention of preserving it just so, but also transported it across Europe, his personal stage set. Freud and his family have curated his history. But as the Guide Book says: ‘Freud cannot be reduced to a private individual’ and then adds a quote from W.H. Auden: ‘he has become a climate of opinion.’ Earlier in the day I had visited Lord Leighton’s house in Kensington. He had no immediate family, and after his death all his possessions were sold. So much of what there is on view has had to be recreated including parts of the famous Arabian décor. Many of the rooms are used for an exhibition of paintings by Lawrence Alma Tadema, and including some by his wife Laura. The Alma Tademas are far more present than Frederic Leighton. Alma Tadema’s huge extravagant canvases of classical scenes have been a tremendous source of dramatic reference for filmmakers and, so, are once more in vogue. Who would have thought, fifty or sixty years ago, that Alma Tadema, a once distained Victorian painter, would create such interest? Public taste is an odd thing. |

Victoria Manthorpeauthor and feature writer Blog

Your email will only ever be used to send you new posts and you can unsubscribe at any time. For more information, please check Victoria's privacy statement.

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|